For 12 years, every time I came to visit New York, it was with one constant companion: an indispensable guide book by Michael Middleditch called the New York Mapguide. Then I moved here one month ago, and almost instantly lost it.

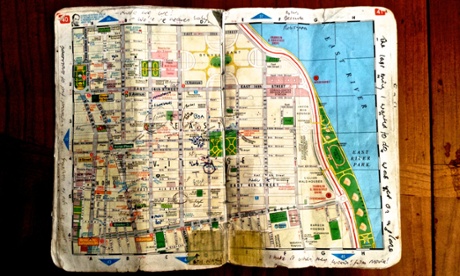

A slim and colourful street map written and illustrated by the former chief cartographer of Geographia, the book leaves ample room for notes and, over the course of a number of trips, I gradually began to mark down in the margins, in the gaps between streets, across the blue expanses of the Hudson and the East river the locations of bars, restaurants, hotels, barbers, art galleries, friends’ apartments and other places I would visit, along with notes about where I was going, who I was meeting and at what time. It was the pre-smartphone era.

On its increasingly battered and taped pages I noted down locations I wanted to use in a short story or a novel, snatches of overheard conversations – “Now I know why they call it Dumbo – ‘cos you’d have to be a fucking idiot to live there” – and graffiti such as “Re-defeat Bush.”

Marked on there was the bar in the East Village where I joined an incredulous and angry crowd as the 2004 election results began to signal victory for George W Bush, the jubilant bar in the Lower East Side where I watched Barack Obama’s acceptance speech in 2008, and the apartment near the United Nations building from which I liveblogged his second presidential victory in 2012.

Whenever I returned to the city, flicking through the pages of the Mapguide would help me instantly locate myself in the New York of my memories, as well as the physical city around me. On one page the Chelsea International Hostel – the first place I ever stayed here, over a decade ago – is circled just a few streets away from the cross indicating the building I moved in to when I emigrated to New York in March this year.

When my girlfriend came to visit soon after that, I picked up my map book as usual to show her around the city – as a local now for the first time – and, after a leisurely day and evening spent on a meandering walk through the Upper East Side and Midtown, across the Brooklyn Bridge and through Dumbo and Williamsburg, I realised with a sinking sensation I had mislaid the Mapguide somewhere along the way. It was gone.

It’s an exaggeration to say I felt lost without it – after all, I have Google Maps on my phone now, which also remembers places I have visited before, and unlike the New York Mapguide can suggest a route and a mode of transport and tell me how long it will take to get there. But without the familiar annotated pages of my Mapguide I found the streets hard to visualise as I planned a journey, found it hard to remember where neighbourhoods were in relation to one another, and what we might see along the way.

Middleditch’s guide is no Time Out or Lonely Planet; the author, who died in 2012, makes no pretence to be objective, and writes with breathless and very personal enthusiasm about the New York he loves, beginning by explaining his decision to choose the Big Apple for his next book after having written a guide to London:

It was not hard to make New York my choice, for it gave me the chance to fulfil my early dreams in the city that epitomized for me at that time all that could be attained: like ‘Hoppity’ who had found a new life at the top of a skyscraper in my favorite cartoon, I too wanted to see this new life.

In reality the lights were out in London and the aftermath of World War II had brought austerity to life in England. For this late traveller New York - Manhattan - in those days meant freedom, great noble skyscrapers (the tallest in the world) and music: the music I liked so much - the music that saw no reason to be the same every night. For me Manhattan was the real home of jazz …

Yes, I like New York.

The book was a product of its time. My edition – the third edition – was published in 2002, and like the city itself in that awful period was palpably scarred and traumatised by 9/11. The page showing the financial district was blanked out from Vesey Street to Liberty Street. The words “MAJOR DAMAGE” were superimposed over the site of the World Financial Center, and to the east, printed in red over the outlines of the Twin Towers, was the stark description “DEVASTATION AREA”.

On the larger scale map of the whole city, “TWIN TOWER SITE” was marked with a red explosion symbol. And on the subway map the southern tip of the 1 train, from Chambers Street to South Ferry, was represented with a grey dotted line, a box warning that those stations were “out of service indefinitely”.

Middleditch – whose son and daughter were working in the World Trade Center less than a week before the al-Qaida attack – addresses the event with raw emotion in what must have been a 2002 addendum to his section on the history of the city: “No one could ever have imagined what tragedy the dawn would bring to the world on September 11th 2001 when a group of insane extremists flew the hijacked planes into the Twin Towers.”

The distress in his language and the broken landscape of the downtown maps reflect something of the feeling I remember in the city in the months and years following the attack – particularly around the “devastation area”, now, as Ground Zero, knitted back into the city as a memorial, a museum, and a defiant replacement skyscraper, but then a wound, a mass grave, a site of confusion and pain impossible to reconcile with the buzz and excitement of the metropolis around it.

Over the next week I retraced my steps to try to find my book, returning to many of the places we had visited that day. The bar staff of the Wythe hotel in Williamsburg, where I seemed to have a memory of consulting the book to help identify some of the skyscrapers facing us across the river, had not been able to find it. The waiter who had served us dinner in the Local 92 restaurant in the East Village said we hadn’t left anything behind.

But in the Brooklyn Roasting Company cafe near the Brooklyn Navy Yard – ironically an area not covered by Middleditch, who largely takes the traditionalist pre-hipster approach that New York equals Manhattan – there it was, sitting behind the cash register: bent, torn, scrawled upon, irreplaceable.

“I’m not going to lie to you, we read through the whole thing,” the young man working there told me, smiling. “We were trying to figure out who you were. We were wondering if you lived here. The address in the front” – the address of a flat in north London I’d left in 2005 – “we were going to send it back to you, but we didn’t know if you still lived there.”

I shook his hand, and the hand of one of his colleagues, and made my way back across the Manhattan Bridge and into the familiar territory marked out on my map, Middleditch’s words in my mind: yes, I like New York.