Moses's Tabernacle, Achilles's battlefield bivouac, Tony Blair's Millennium Dome: the history of man is tightly entwined with the history of the tent. Persian yurts date back 2,600 years, the Bedouin have lived in black bayts for centuries – and, following the second world war, the Norwegian Sami people briefly returned to living in lavvus after the Nazis burnt down their houses.

But, according to one creation myth, the world's oldest tent may well be the native American tipi. "In their creation stories, the Dakota tribe were coaxed into emerging above the surface of the Earth by a mysterious trickster," explains Emil Her Many Horses, curator of the USA's National Museum of the American Indian. They were naked and had nowhere to live, until another mysterious figure taught the Dakota to cover themselves with animal hides. It's these covers, says Her Many Horses, which might possibly represent the origin of the tipi myth. And whatever the myth's veracity, Canadian scholar Ted J Brasser believes that a precursor to the tipi was invented about 5,000 years ago.

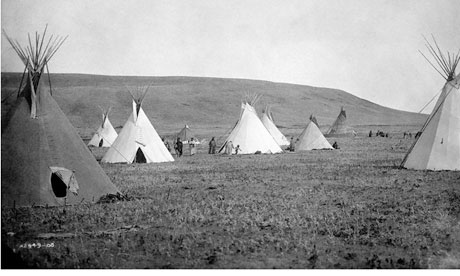

The full-sized tipi – not to be confused with the less mobile wigwam – was made from as many as 18 bison hides, supported by 15 wooden poles, and often stood at more than 5m (16ft). Exact designs differed from tribe to tribe, but tipis were always conical in shape, and had a hole in the roof which acted as a sort of chimney. In winter, an inner lining would be fixed to the tipi to increase insulation.

And what lay within? A fire took centre stage, around which the family kept a strict seating plan. "Men slept always around the north side, women around the south side," Her Many Horses explains. "The door was in the east, facing the sun, and the guest of honour would sleep in the west, opposite the door." Tipi maintenance was considered the domain of women. It was they who tanned the bison hides, sewed the hides together to create the tipi's coating, and usually painted it with geometric decorations – though men sometimes chipped in with depictions of battle scenes.

Her Many Horses reckons it would take about 20 minutes for a skilled practitioner to set up a tipi. And according to Laura McDowell, assistant curator of collections at the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian in Illinois, such dexterity was ingrained from childhood. "Kids were given tiny toy tipis to help them grow accustomed to handling them."

Once up, though, it wasn't long before tipis were dismantled. Her Many Horses says: "A tipi wouldn't be left in the same place for more than a couple of months, due to the danger of attacks from other tribes." And so the bison hides would be packed into special bags by women, and carried to the next location by horses – who also dragged along the wooden poles. The hides themselves lasted between one and two years – depending on whether they'd been smoked. As Her Many Horses notes, "Smoked hides were waterproof, and so lasted longer."

But by the 1880s, tribes were forced to replace animal hide entirely. European settlers brought westwards by railroad expansion had begun to cull thousands of bison – and so their skins gave way to canvas. And by 1900, the residential tipi itself became virtually extinct. Many native Americans had been forced into reservations, and were encouraged to live permanently in wooden houses. The tipi is survived by the Asian yurt, which is still lived in by millions.