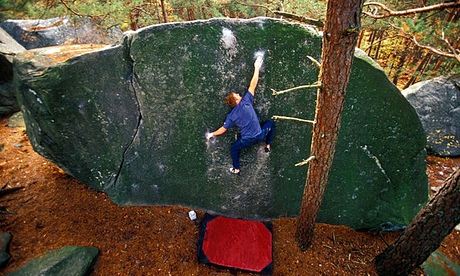

One thing you quickly learn when you go bouldering – a sort of low-level rock climbing done without ropes – is that you can find yourself in a pretty sticky situation even when you’re just a few feet off the ground.

This thought flashes through my head as I swing my left heel up and on to the top of the 2.5-metre-high hunk of sandstone I’m attempting to climb, praying that my right toe stays glued to the centimetre-wide ledge of rock the rest of my body is balancing on.

This time I’m successful. I haul myself over and stand up proudly, only to find a pair of French kids already sitting there enjoying the view.

It’s my first visit to Fontainebleau, a region of rocky gorges 60km south-east of Paris that’s widely considered the best destination for bouldering in the world. Climbers of all ages and abilities travel from around the world to visit this tranquil pine forest populated with impressively active French outdoorsy types and thousands of spectacular boulders, with no fewer than 20,000 routes to climb.

From the end of the 19th century Fontainebleau – Font to Brits, Bleau to locals – was a training site for Alpine climbers. Now, bouldering as a standalone sport is growing in popularity, appealing to those put off by the price of mountaineering equipment – or perhaps just lacking a head for heights. And Font has become a must-visit destination for those who enjoy the climbing challenge but may have no interest whatsoever in tackling an actual mountain. The minimal kit requirements – tight-fitting rubber-soled climbing shoes, chalk to keep your hands dry and a crash pad (a kind of foam mattress) for safety – make it a relatively accessible pastime.

Although organised tours are available (Wales-based Rock and Sun offers one-week trips from just £550) I make the relatively straightforward journey across the Channel with three friends – all of us first timers to Font – by car, booking a cheap gîte through Airbnb.

The first “chaos” of boulders we visit is called Bas Cuvier (there are 15 or so main clusters within the forest). With crash pads strapped to our backs, we look like turtles with foam shells as we march from the car park into the maze of rocks and ferns. Following an obsessively detailed guidebook (see ) and the heiroglyph-like dashes of coloured paint on the boulders, denoting the various grades and types of route, we eventually reach a rock worth climbing ... and spend the next 40 minutes trying to work out how to do it.

Even with crash pads and the group taking it in turns to “spot” – standing behind the climber with hands out to make sure they don’t hit their head if they fall – there is some danger; simple moves feel increasingly daring as you ascend. Fortunately the only disasters we experience are scratches, stubbed toes and bruised shins.

For three days we roam around, spoilt for choice as to what to climb, using our guidebook to track down boulders with the best routes within our grade range, or simply those with unusual and appealing shapes.

On the second day, in an attempt to find a particular spot at Apremont (technically only seven minutes walk from the car park) we end up on an accidental three-hour hike through the forest before we reach our destination, and the day after we find ourselves climbing in a dark, overgrown patch of scrub without another climber in sight.

In between climbs we lounge on rocks like basking lizards, eating baguettes and camembert while observing some of the bizarre sights of the area: hulk-armed climbers frantically scrubbing for handholds with what look like toothbrushes, and tanned locals wiping their feet on doormats to get bits of grit off the soles, in order to get a better grip on the rock. We even spot one elderly climber enjoying a cigar atop a rock.

“Don’t get too hung up about the grades,” a Font regular advised me, and this proved to be the best attitude. The real satisfaction of bouldering comes from figuring out how to complete a route – a trial-and-error experience that’s like doing a physical jigsaw puzzle – and proudly massaging your red, calloused and grazed hands as you hobble home for the evening, to sip on a well-earned beer.

Up and away how to plan your bouldering trip

Before you go

You can buy shoes and chalk at climbing centres or sports shops including Decathalon (there’s one at the Villiers-en-Bière near Fontainebleau). Crash pads can be hired from climbing shops in Fontainebleau, from about €8 a day: try S’cape (scape-shop.com) or Sport Outdoor (sportoutdoorfontainebleau.com), and do check availability in advance at weekends and holidays.

Fontainebleau Fun Bloc (Jingo Wobbly Publishing, £30) is a good all-round guide book, with 7,000 routes, 17 kids’ circuits and all the maps you need to find each spot and navigate the boulders. It also has photographic maps of each boulder with routes marked, which makes climbing more straightforward – once you’ve got your head round the symbols.

Getting to Font

Because the bouldering spots are spread around 900 sq km of forest, it’s useful to have a car when visiting Fontainebleau. Eurotunnel fares from Folkestone to Calais start at £55 for a car and passengers, returning within five days. Fontainebleau is about 3½ hours’ drive from Calais or one from Paris. The Boulder Bus from London to Fontainebleau costs £249pp for a weekend sleeper, including all on-board accommodation.

Where to stay

For home comforts each evening, there are several self-catering gites in Fontainebleau forest. The Maisonbleau complex near Buthiers caters for climbers, with crash pads to hire and prices from €300 a week for a gîte sleeping four. At the Haras de la Fontaine complex (france-gite-fontainebleau.fr) in the village of Poligny, south of Nemours, prices start at €208 a week for a gîte sleeping three. Campsites such as Camping Les Pres camping-grez-fontainebleau.info) south of Fontainebleau and Les Courtilles du Lido (les-courtilles-du-lido.fr) on the forest’s eastern edge have tent pitches from around €6 a night. Airbnb has a selection of budget accommodation in the town and forest, from about £40 a night for four.

Tips for first timers

“Top-outs (the final move, when you climb on top of the boulder) can be scary and slopey, but good crash mat placement is key for confidence. On top of this, don’t expect to climb at the same level as in Britain (the grading is tougher in France) and prepare to be spanked [really challenged] ... but this makes succeeding all the better.”

• Bethan Thomas from womenclimb.co.uk, who visited Font for the first time this spring

“A topographical guide can be helpful, but for your first visit to Font it is much better to be with a local guide who can show you the best circuits according to the weather and your level. As for safety, bouldering in Font is nothing like a climbing gym: the risk of falls should not be underestimated, and make sure you borrow a crash mat.”

• Jean-Pierre Roudneff, editor at bleau.info

“Font can be overwhelming because there are so many boulders to choose from. Don’t run around trying to climb them all; just pick one and work at it. Although you will be tempted to keep climbing, have a rest day after a couple of days to let your hands heal, and make sure you use good hand cream at the end of each session. And don’t be put off when locals make everything look so easy: they’ve been climbing the boulders at Font for years.”

• Gabriella Stewart, 15, a Scottish climber who has been bouldering at Font for five years