Santa Marta

They are proud of the bronze Michael Jackson statue that stands on the edge of a little square in the Santa Marta favela in Rio de Janeiro. "It's the only one in Rio," said 32-year-old Thiago Firmino, DJ, local resident and our tour guide. Its arms stretch out to embrace a dizzying view of Rio, and of the shanty town that tumbles down the hillside below. On the wall behind it is a Michael Jackson mosaic.

It was here that director Spike Lee filmed scenes for the video to Jackson's 1996 hit They Don't Care About Us. Rio authorities originally opposed the video because they felt filming in a favela would show a negative side of the city, which at the time was bidding to host the 2004 Olympics. Nearly two decades later, with both the 2014 World Cup final and the 2016 Olympics set to be staged here, Rio is no longer quite so ashamed of its favelas. Officially, it has 763 of them, (according to the 2010 census), and they are home to almost 1.4 million people, or 22% of the city's population.

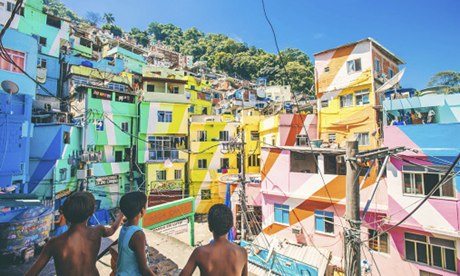

Lee's video plays on a loop in the little tourist shop that Thiago's parents run on the square, Praça Cantão. The alleyways in which Jackson danced seem little changed but lower down, a square at the foot of the favela has been brightened up with a 7,000-square-metre lick of paint. The Favela Painting art project, created by Dutch duo Haas&Hahn, with the aim of boosting community pride, has seen 34 houses painted in a rainbow of bright colours.

In 2008, Santa Marta was the first favela in Rio to be "pacified" under a state programme to expel its drug gangs by installing a police base and initiating social change projects. Since then, another 34 favelas have been pacified. Santa Marta is held up as the model and has become a stop-off for visiting celebrities, Madonna, Beyoncé and Alicia Keys included.

They come to see the effects of pacification: creches, new houses, concrete steps instead of treacherous muddy tracks, and a free tram that glides up at a 45% angle to help its 6,500 or so residents get up and down what is essentially a 1,000m mountain covered in rough brick, breezeblock and even wooden houses, just below the Christ the Redeemer statue.

In what used to be one of Rio's most violent slums, residents are turning to tourism. That day, Thiago's clients were two Dutch tourists from Utrecht, and he had recruited student Pedro Monteiro, 18, to translate. The Dutch visitors wandered wide-eyed through the favela.

"I like it very much," said Mirko van Denderen, 33, a teacher. "The strange buildings …"

Both peeked into Thiago's house, impressed by the contrast between its rugged raw-brick exterior, and its neat living room, fitted kitchen and flat-screen TV.

"The majority of houses are cool inside, all done up," said Thiago. "It demystifies it."

Tours like Thiago's offer a glimpse of another side of Brazilian life. But tourists should be aware that these are tours of places where very poor people live – which some might find difficult. It's very useful to have guide who lives in the area: they'll be accepted by local people, and are unlikely to gloss over issues the favela faces.

Pedro pointed out handmade signs protesting at the forced removals of dwellings that perch precariously at the very top of Santa Marta. "Property speculation," said Thiago.

This used to be one of Rio's most violent slums, and was controlled by the Commando Vermelho (Red Command) drug gang. Now, like Thiago, residents of pacified favelas such as this are turning to tourism. "I had to accept the work because so many people were coming," Thaigo said.

Roberto de Conceição, 48, was carrying his shopping up the hill. He likes the tours, he said: "We meet new people. Thiago is from here," he said. Paulo Roberto, 45, was selling mobile phone cases, pens and Santa Marta T-shirts designed by his 11-year-old son, on a little stall. "We are more and more involved. I live from this now," he smiled.

The alleyways got narrower as we descended. Chickens clucked in a drain. Purple flowers sprouted near bags of gravel. Children in flip-flops pushed past talking football. An old woman was carried past on a chair. Humanity teemed in the narrow alleys. Everything was tiny: a barber shop, an electrical products stall, a bedroom with three small bunk beds.

"Every part of the community has a name," said Pedro, as he paused in front of a wall. "This was called Beirut." The building behind which traffickers used to hide is now used for boxing and judo.

At the foot of the favela, outside the Bar Cheiro Bom (Good Smell Bar) Pedro pointed out bullet holes in a wall.

"This was a conflict zone," said Thiago. "Now there is always a police car and a camera."

The Dutch visitors were taken back up the hill on the tram. "It feels a little strange to be wandering around taking pictures," concluded bank worker Willem van Duuren, 41. "It feels a bit voyeuristic, seeing how poor the people are, but it is part of the country."

• Local resident Thiago Firmino offers two-hour tours of Santa Marta from around £15 in Portuguese or £20 in English (+55 21 9177 9459, favelasantamartatour.blogspot.com.br)

Vidigal

Vidigal is Rio's most foreigner-friendly favela, with pousadas (guesthouses), bars, restaurants and even a sushi joint aimed at the tourist market. It is relatively small and picturesque, with spectacular views over the Atlantic, and an hour-long walking trail that winds from its upper limits to the top of the Dois Irmãos (Two Brothers) mountain.

When pacified in 2012, Vidigal was already popular with artists, young Brazilians and foreigners. Scottish school librarian Graeme Boyd, 34, lived there for two six-month periods, in 2009 and 2011. "As long as foreigners respect the locals, make a contribution and use the businesses inside the favela, they will be welcomed," he said. "People reacted to me as if I had lived there all my life."

Today Vidigal is compared to Rio's bohemian Santa Teresa district. This is a favela undergoing a gentrification process, with all the property speculation that entails. Critics say locals are the losers in this process. A legal battle over ownership of its most famous pousada, Casa Alto Vidigal – between Austrian proprietor Andreas Wielend and its previous German owner – even made the newspapers. But that hasn't diminished its popularity.

Casa Alto Vidigal looks like a squat transplanted from Dalston, east London, and offers rough-and-ready accommodation. But its all-night electronic music parties and Sunday sunset DJ sessions on a terrace with breathtaking views over Leblon and Ipanema beaches have made it a landmark. On weekend nights, young tourists queue for motorbike taxis to climb the hill to Alto Vidigal and other electronic music parties such as Morro Eletronico – an Ibiza-style lounge bar, whose outdoor dance floors and terraces cling to a tropical hillside.

• Carioca Free Culture (+21 99800 6278, cariocafreeculture.com) is run by Brazilian Rodrigo, who grew up in the neighbouring Rocinha favela, and his partner, American Mary Ellen. Their Dois Irmãos Trail in English lasts three to four hours and costs £15pp (minimum two people). It starts and ends in Vidigal and includes a hike up the mountain

Tavares Bastos

Vidigal is not the only favela with nightlife credentials. Monthly jazz nights at the Maze Pousada have put the Tavares Bastos favela in Catete, central Rio, on the city's nightlife circuit. Staff hold up signs to direct the hundreds of partygoers who flock down the favela alleys. The live music is excellent but the 40 reais (£11) cover charge makes it too expensive for most locals; instead foreigners and richer Brazilians cram in. The pousada is owned by British expat Bob Nadkarni, and his son also runs a monthly alternative rock night, called Labirinto.

Bob has been tinkering with and expanding the building for the 30 years he has lived there, and opened the pousada seven years ago. It now teeters over the favela like a Gaudí castle, full of stairways and corridors and hidden nooks and crannies, with panoramic views over Guanabara Bay from its ample terraces. It has five double rooms and a dorm.

The neighbouring police training base has long made this favela relatively safe – on a recent visit, officers holding automatic weapons were practising combat drills in the alleys around the pousada.

"People who come here don't want a common, tourist hotel that might be more comfortable, with air conditioning and TV," said Bob's wife, Mariluce da Silva. "It is very tranquil."

Complexo do Alemão

Mariluce was our guide to the Complexo do Alemão favela in north Rio. When soldiers and police invaded in 2010, a TV Globo helicopter showed dramatic live footage of bandits brandishing rifles and machine guns as they fled up a dirt track from advancing security forces. Now Alemão, a vast complex of 13 favelas, has a six-station cable car that has become a tourist attraction. The little gondolas glide silently over the concrete roofs, water tanks and satellite dishes of this vast favela, while sounds of dogs and chickens drift upwards. The teleférico, as it is called, opened in 2011 and a ride costs £1.40 for tourists (residents pay just 28p). And while some complain that the opening hours – 6am-9pm weekdays and 8am-8pm weekends – suit tourists rather than locals, the cable car is still better than cramming into the rickety minibuses that criss-cross the favelas for twice the price.

Complexo do Alemão, literally "the Complex of the German" was actually founded by a Pole – but blond, blue-eyed gringos are invariably refered to as "Germans" in Brazil. At the cable car's last stop, Palmeiras, resident Jackson Menezes, 74, was sitting in the sun. "God blessed all the residents who live here who use the cable car. It really helps the community," he said. Menezes supported pacification, but said that the drug trade for which Alemão was notorious continues surreptitiously: "It doesn't stop. It never stops. It stays hidden."

Beside him a boy was selling water. He said in English that he was 11 and his name was João. He was barefoot. João said he goes to school in the mornings and sells at the station in the afternoons. "It's good. It's profitable," he said.

Cleber Araújo, 36, was minding his souvenir store. "I am against cable-car tourism," he said. "It is a safari."

Instead he organises group walking tours of favelas. A group of 70 have just been from a South African university, and 107 Spanish visitors have booked for the World Cup.

Out here in Rio's gritty, dirty, industrial Zona Norte, far from the beaches of Copacabana and Ipanema in Zona Sul, the community is clearly much poorer than in Vidigal. Many roads are just dirt. Three rangy horses were grazing on waste ground. Children passed with a horse and cart. Mariluce advised us not to take photographs as we looped through one alleyway in a part of the favela called Inferno Verde (Green Hell).

Tourist Alejandro Barreneche, 31, from Colombia, stopped to buy beer at a hole-in-the-wall bar. "It's like going into a reality TV show," he said, "like a zoo feeling. But again, it allows you to be closer to reality."

Barman Leoni Franco, 24, shrugged: "It's good that tourists come. After pacification it is 100% better."

Other residents seemed more surprised by the visitors than the visitors were by them. Police were patrolling the streets, hands on the triggers of their automatic weapons, like an occupying army. Residents averted their eyes: from them, from us.

Mariluce stopped to point out an electricity meter, installed by the Rio electricity company after pacification. Previously, residents hooked up illegally with homemade tangles of cables called gatos (cats). The electricity meter is called a tigre (tiger). "We used to steal from them," smiled Mariluce. "Now they steal from us."

For decades, the people of Rio's favelas lived in gang-controlled isolation. Fear of the drugs trade that dominated so many of these neighbourhoods kept middle-class Brazilians away. Now that is changing. And the rest of the world is arriving. This throws up interesting questions – for those living there, and for those visiting. A curtain has come down.

"We didn't have all these visitors," said the owner of a tiny shop. "But no one gets annoyed. I hope it continues."

On a little high street similar to many in Brazil. Mariluce shooed her tourists out of the way of a minibus. "As you can see, this is a neighbourhood like any other," she said.

• Cleber Araújo (+55 21 96736 9353, complexoalemao.rj@gmail.com) offers group tours for £15pp, with English translation and cultural options such as capoeira and samba, and even lunch at a new favela bistro