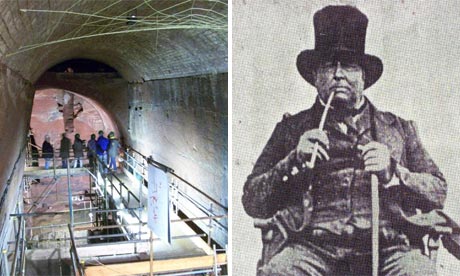

Joseph Williamson was an intriguing fellow. Born into poverty in 1769 he picked himself up by his bootstraps, set off to Liverpool to seek his fortune, donned a pink suit to marry a wealthy tobacconist's daughter and then, for reasons only known to himself, set about digging a series of tunnels the purpose of which remain, to this day, a total mystery.

"There are two theories," Gordon Hunter, chairman of the Friends of the Williamson Tunnels, tells me, "that he had them dug to keep men returning from the Napoleonic Wars occupied, or that his wife came under the influence of a lunatic preacher who told her the apocalypse was coming and she persuaded Joseph to prepare chambers for underground living."

Either way, it's clear that Joseph, dubbed the "Mole of Edge Hill" had a penchant for eccentricity.

"There was a trapdoor in his basement," Gordon says, "and it led down to underground rooms and tunnels. He had a large fireplace and there are vents everywhere."

"Why did he want to live underground?" I ask.

"No idea," says Gordon, with a shrug. I like Gordon. He's a retired engineer with watery blue eyes. I don't think he stops smiling once for the whole time I'm with him.

Williamson was, you've gathered, quite the character, with clear liking for the frivolous and mischievous. Despite being a millionaire he once met King George IV in nothing more than a pair of tatty corduroy trousers, hobnail boots and a patched coat. He would throw banquets where he would pretend to serve beans and bacon simply to see who his real friends were.

The thing I find the most remarkable is that until just over a decade ago, the Williamson Tunnels were regarded as something of a myth. Everybody had heard of them but nobody believed they existed. But a chanced-upon article, written in 1925, lit the fire of curiosity once more. "A man called Charles Hand found the entrance to one of the tunnels," Gordon explains, "and he wrote that he was able to walk underground for over a mile. We've only scratched the surface," he says, gesturing down into a hole I am about to descend in Edge Hill. "We think there are three layers of tunnels. At least."

"It was brilliant when we were finally allowed down here," says another volunteer, Les Coe, passing me a hard hat. "It was like finding Tutankhamun's tomb. Best day of my life."

Currently there are two excavation points. There's one the public can go down, at the Williamson Tunnels Heritage Centre, and then there are the tunnels being actively cleared by the volunteers. Every Saturday and Sunday they come and undertake the slow, laborious task of taking out more than a hundred years' worth of rubble and debris poured down holes by bakers, jam makers and housewives. Every bucket is pored over for small treasures and they're doing all this purely for the love of local history and preservation.

"It's been a long fight to be able to excavate these tunnels," says Gordon with a rueful nod. "Ten years it's taken us to get permission. But now we have."

The good news is that the rubble, they think, will only be in the top layer of tunnels. As soon as they have excavated those they should, in theory, have unfettered access to the second and third layers.

"We know they go down at least 90 feet," says Les, his eyes bursting with enthusiasm.

Sadly, I can only go down to the top layer, but the brickwork is exquisite and the volunteers' curiosity is infectious.

"There are narrow tunnels," Les explains, "some no wider than a metre, but then suddenly, they open out into massive spaces. It's magical."

No doubt about that. Les and Gordon are the last of the great explorers. There aren't many places left on earth that are yet to be discovered but there's a small corner of Liverpool that still harbours a great secret.

• Guided tour of the tunnels from the heritage centre (Smithdown Lane, 0151-709 6868, williamsontunnels.co.uk, adults £4.50, children £3, family ticket £14). The friends of the tunnels are always looking for volunteers

Follow Emma on Twitter @EmmaK67