The contrast always seems so severe. You start down in the valley: it's steep-sided and dark, choked with lines of sooty stone houses that press up against the canal, the road and the river. Then you blast up through some woods and emerge in outer space, a place filled with light, cloud and long views. No wonder West Yorkshire has been jangling the literary nerve for generations, squeezing prose and poetry from residents pent up in the valley but with a yearning for the hills. Now I'd come out with friend and part-time poet Peter Finch, who lives locally, to find a few verses that had escaped up on to the moors, words written by Simon Armitage that have been inscribed on six rocks across a 47-mile route that snakes through the territories of Ted Hughes and the Brontës.

We started at Marsden, birthplace of Armitage whose energies have certainly blasted him out into a diverse artistic freedom: operatic libretto, translations and novels along with the poetry – and always that distinctive and humorously gritty style. Who else would start a poem, "Harold Garfinkel can go fuck himself"? I couldn't think of a living poet whom I'd more like to see scratch his lines into the landscape.

We walked west along the A62, then scrambled uphill from the valley. Above us, lining the edge of moorland, were some old quarry workings. We began our search, but for what? We didn't really know. Had Simon and his stonemason, Pip Hall, left a gnomic single word, hidden on some obscure stony shelf, or were we to expect grandiloquence, great striding lines of lyrical exposition shouting at the sky?

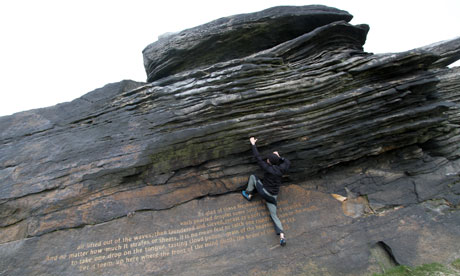

For the moment, Peter was more interested in the rock climbing possibilities." There is chalk on these ledges. Someone's been on it." He donned his rock shoes (Peter always carries shoes for every occasion) and had a quick experimental foray upwards. He is pretty nimble, but when he reached the level at which a fall could be fatal, he gave up and descended. "No sign of any inscriptions up there."

We scouted further afield. The old quarrymen had done some mysterious things up here: what were those curious rounded hollows in the rock face? Why had they put this great wall of slabs across this ledge? We skirted around it and found a newly constructed stone seat, inscribed "Stanza Stones poetry project".

Behind the tussock-topped slab wall we spotted the verse. Entitled Snow, it snaked across a rock face in four lines, a marvel of stonemasonry in the way it coped with the uneven textures and facets of the stone. Already dusted with green moss, it was becoming part of the landscape.

The big question, of course, with any graffiti, is: does it warrant the remarkable hubris required to engrave it on the landscape? Forget whether Arts Council funding is involved: does it cross the border and move beyond mere vandalism? Would the Ramblers Association approve? Would Banksy? Would it dare to annoy anyone?

We read the stanza several times. That required moving along it. We furrowed our brows. Peter muttered approvingly about "registers" and "internal rhythms"; I muttered about how I'd forgotten my gloves. A light dusting of hail began to fall. Then we each delivered our verdict. We liked it.

I'm not going to repeat the verse. It took Armitage and Hall a lot of effort to haul those words up into that remote and chilly corner of a forgotten quarry, I will not drag them down again. Suffice to say that Snow had the essential elements of grit, lyricism and a few snags of the unexpected. There was not, however, any whiff of controversy, a slight disappointment to me.

Now for Number Two, which was a long yomp along the Pennine Way with big skies and far-off smudges of cities and as much weather as one could wish for in a year: sun, sleet, rain, hail, then more sun. After the White House pub above the town of Littleborough, the Pennine Way takes a long curving route around the moor's edge. The second stanza is Rain, this one cut into an outcrop that glowers out at the weather, its strata bunched and puckered with the effort. Hall did another sterling job here, mirroring the sinuous rise of the strata and working around the toeholds of rock climbers who train on it. Memorable phrases rang out to me, such as a "up here where the front of the mind distils the brunt of the world".

We had more inscriptions to enjoy at Stoodley, a huge stone memorial to mark the end of the Napoleonic Wars. And into it – would you believe it? – those naughty tykes have been carving their names for a long time. The first vandals arrived soon after the structure was rebuilt in 1856. I particularly admired those who brought tools or a stonemason with them. You can imagine their voices echoing inside the gloomy spiral staircase that leads, in total darkness, to a high balcony: "If a job's worth doing … " Will passersby one day read Armitage's stanzas and have a similar experience?

The clock was approaching nine – when we finally reached a pub, Stubbing Wharf in Hebden Bridge (King Street, stubbingwharf.com), a place where Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath spent a memorably grim evening which Hughes recorded in Birthday Letters: "If this was the glamour of the English pub it was horrible." Happily the pub has long since improved.

Next day it was bright sunshine and we climbed up out of the valley again and wandered into a labyrinth of old quarry workings before emerging, quite abruptly, on a marvellous panorama over Oxenhope and Haworth. A few feet below us, laid in the bilberry bushes like some lost tribute to Ozymandias, was our third stone, Mist.

This inscription is done in limestone and the words appear to catch the light, reverse themselves and rise from the rock, hovering in the air like the very subject matter they so well describe.

There are three more stanza stones that are mapped and relatively easy to find, all within walking distance of Ilkley. Simon Armitage is clear about what he wants, "I hope the Stanza Stones act as beacons of inspiration, encouraging people to engage with West Yorkshire and Lancashire's great outdoors in thought, word and deed."Then there is one more stone, so he says, that is somewhere out there, the lost seventh stanza. Even now it is gently sinking behind a veil of moss and oxidation, perhaps never to be found. I think, however, we are all going to have lots of fun searching.

• Download a trail guide at ilkleyliteraturefestival.org.uk