There is a special feeling when you give that final turn of the key in the lock and set off on a house exchange. A faint wondering, alongside the travel excitement, if you are doing something rather unwise. Who are you about to allow into your home? Are they, at this very moment, speeding down the motorway in a removal truck? Will you arrive at your exchange destination to find the door barred? Or to find no house at all? This time my feeling of uncertainty was a little stronger, if only because our destination was less settled than any we had visited before. We were going to Morocco.

We live in Rome, a city we love, but love rather less in July and August. By late June we find ourselves dreaming of cooler, greener places. Fortunately Rome appeals to people eager to escape their own cool greenery. Summer exchanges have taken us to Vancouver and the French Alps and Pyrenees. We were first drawn to house swaps simply as a means to travel without breaking the bank, but we soon discovered they had other charms. Though we have only met one of the families we have exchanged with, I have the curious feeling that we know them all. We felt welcome in their homes, learned something of how they ordered their lives, and – following their advice – visited their favourite local spots, shopped at their favourite shops and ate in their favourite restaurants. They did the same, in Rome, and during our stays we kept in regular contact, comparing notes.

This year it began to look doubtful that we would do an exchange. By mid-April nothing promising had come up – until a French family wrote, offering their holiday home in Essaouira, on the Atlantic coast of Morocco. The pictures looked beautiful, and included in the swap was a cleaner-cook who, if we gave her some money to buy food at the market, would make us breakfast and dinner: unheard-of luxury for a house exchange. Our children had never been south of Europe, and though I was doubtful about the heat, Morocco would be an exciting new experience for them. For that matter it could be an exciting experience for their parents: to get a glimpse of the Arab spring at first hand.

The prospect seemed less enticing soon after we agreed the swap, when we learned of the horrors of the Marrakech café bomb. I suspect the chief peril of house swapping is not vandalism or robbery, but that your exchangers will suddenly change their minds, leaving you with a fistful of air tickets and nowhere to go. In this case, though, we never thought seriously of cancelling. The bomb seemed an isolated event.

Luckily this proved to be the case. Arriving in Marrakech, the greatest dangers seemed to be the 45 degree heat, the motorbikes roaring through the maze-like alleyways of the souk and the "guides" who would lead you in endless circles around the old town to earn a good tip. The city, though a visual feast, was a place where affluent foreigners met poor locals head on, and it showed. The first casualty – at least for the westerners – was reliable information. All facts, from the price of a pair of slippers to the best way to get to the coast, were complicated by hopes of money. Fortunately, even in Marrakech, 100 miles from our house-swap destination, we were helped by our exchange, who had given us the number of a contact in Essaouira, Hamsa. When we rang him he quickly arranged a comfortable car at a fair price.

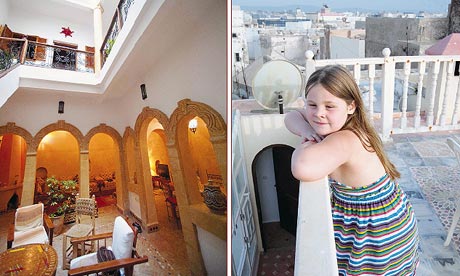

So we reached our new home. The house was beautiful – even more so than in the photos on the exchange website – and intriguingly tall and narrow, like an upturned matchbox. Stairs rose vertiginously to a small roof terrace from where you could see Atlantic breakers crashing on to the rocky shore. The house was also a little damp, but this, as we quickly realised, was a hazard of Essaouira. The town is renowned as a windsurfers' paradise. As such it is buffeted by fierce winds, which become decidedly chilly by evening, and we found ourselves short of warm clothes. The sea, too, was cold, and all in all it felt a little like Cornwall with camels. At least we didn't have to worry about searing heat. In all other respects, though, Essaouira proved an excellent destination. It allowed our children, who had been rather discouraged by the hassle of Marrakech, to discover a gentler Morocco. Our cleaner-cook, Hayat, was warm and friendly, as were most people we met in the town. I was struck by a sense of old-fashioned neighbourliness; café bombs seemed very far away here.

Another surprise was the variety of lifestyles. As we sat on Essaouira's beach in the bracing wind, I was surprised by how the Moroccan women around us had every kind of appearance, from burqas (fairly rare) to head scarves and flowing gowns, and bare heads and bikinis. What was more, one group might include a complete mix of styles. Though the women mostly kept out of the water (and who could blame them?), leaving the waves to the men, a few waded into the surf in their flowing dresses. There was about the whole scene, I realised, something Victorian.

We met our swappers' contact, Hamsa, and he showed us where to find the town's best coffee and where to eat well. Moroccan food was another great discovery of the visit. It is surely one of the world's great cuisines, and when not enjoying Hayat's fine home cooking, we tried delicious tajines and couscous in local restaurants and ate freshly caught crab and sardines at cafés by the port.

So we got to know our temporary home. My wife Shannon took our seven-year-old daughter to a hamam, from where she returned triumphantly recounting how she had been mud-splattered, scraped and scented and then painted with elaborate henna swirls. In the little souk we spent time in the fish market and looking at fossils and magic boxes. Our son was particularly delighted when a spice stall owner let him hold its resident chameleon (a shrewd sales technique).

All the while Morocco was undergoing a quiet revolution. We had seen it when driving from Marrakech to Essaouira. It was Friday – the traditional protest day – and we saw a good number of demonstrations: processions of cars passing very slowly through dusty towns, passengers holding up huge red-and-green Moroccan flags. In Essaouira everyone we met was eager to talk politics. Their views seemed broadly the same: they were disgusted by the corruption of the country's long-entrenched administration but still had a wary faith in the king, Mohamed VI.

Corruption was visible most of all through what you could not see. It was impossible not to be struck by the scarcity of computers. Though Essaouira had two internet cafés, they barely functioned, as the telephone lines were so poor. In an information age, Morocco had been left by the wayside.

Yet change was coming. The day after the protests a referendum was held on reforms to limit the king's near-absolutist powers. We could see the result – a 98% majority for reform – in the smiles of the people on Essaouira's streets. It was exciting to find ourselves witnesses to this moment of hope.

I need not have worried as I turned the key in the lock to leave our Rome apartment. Our swappers had enjoyed Rome, and we found everything just as it had been.

Essentials

Homeexchange.com, which the Kneales used for their house swap, offers 40,000 listings in 143 countries, with membership schemes from £6 a month. The Guardian's house swap service costs £35 a year; for details visit guardianhome exchange.co.uk