The great rivers of the Indian sub-continent descend through clefts in the Himalaya to arrive at the ocean, thinned by irrigation channels but still huge. The Indus and the Brahmaputra, curling west and east for almost 2,000 miles each, hold the whole land in giant pincers, while the tributaries of the Ganges flood into India's plains. Anyone seeking to follow these stupendous arteries to their origins, labouring northwards through some of the deepest gorges on earth, would arrive in astonishment at a lonely mountain in Tibet. It rises beyond the Great Himalaya on a plateau of lunar emptiness, and its isolation above two brilliant blue lakes lends it an eerie beauty. This is Mount Kailas, holy to one-fifth of humankind.

If it is less known in the west than other holy mountains – Olympus, Sinai, Fuji – this signals its near-mythic remoteness. Tibetan herders and Indian ascetics have been circling its base in veneration for centuries – its summit has never been climbed – but it stands recessed in Tibet's most desolate prefecture. The pagan gods inhabiting the mountain were converted to Buddhism more than a thousand years ago, and Kailas has long been identified in Hindu-Buddhist scriptures with the mystic heart of the universe. Even after the Chinese invasion, during the oppression of the Cultural Revolution, pilgrims circled it in secret.

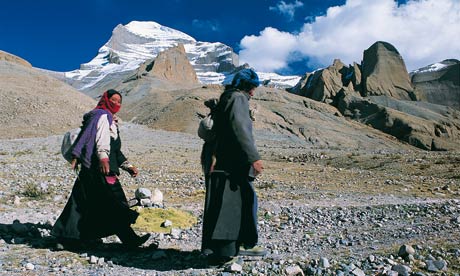

If you trek through western Nepal – as I did – up the valley of the Karnali river, the highest source of the Ganges, you reach the Tibetan frontier after a seven-day hike. A Twin Otter aircraft carries you by stages from Kathmandu to the tiny provincial capital of Simikot (there are no roads) and from here you set out north-west toward Tibet. I went with sherpa, cook and horseman: a small, Raj-like procession which strung itself out along the high tracks. Until a few years ago this region was overrun by Maoist guerrillas, and it is little traversed by hikers even now. The villages along the way are small and poor. As you ascend, their people lose the darkness of the subcontinent and take on Tibetan features, Tibetan dress. Prayer flags fly from the rooftops, and memorial walls appear, their every stone inscribed with a prayer.

On the border, where Chinese officials descend on the few travellers, I came on the first disquieting sign of Hindu pilgrimage: the corpse of an Indian who had died on Mount Kailas, dumped on the track by the frontier bridge before a Nepalese helicopter carried him away.

As we waited for the border guards, a bitter pilgrim – a tough Indian woman from the Himalayan foothills – decried the ignorance with which her people arrived in Tibet. Her government ran a lottery for would-be pilgrims to Kailas, she said, and many were refused on grounds of health. They entered Tibet through north-west India, acclimatising slowly.

But unscrupulous tour agents were also at work. "They often make no medical checks at all," she said. "They'll enrol anyone. They just want the money. The people who sign up don't know how hard it will be. Kailas is holy to Lord Shiva, and many pilgrims are Shaivites from the south, from lowland cities such as Bangalore and Mumbai. They've never climbed anything except their own stairs. Sometimes they're old."

I saw these pilgrims later, deeper into Tibet. They occupied crude hostels, multiple families crammed into small rooms, at the mercy of Chinese officials. Yet they had the preoccupied, exalted look of those on pilgrimage. For they were on their way to Kailas, on whose summit the god Shiva sits in eternal meditation, his goddess beside him. To circle the mountain would lighten their karma, lifting them toward moksha, the Hindu nirvana. They did not yet know the harshness of the four-day climb that awaited them.

My first sight of Kailas was from the 4,500m Thalladong pass in the foothills to its south. This is a sight of planetary strangeness. At my feet stretched the haunted Rakshas Tal – the Lake of Demons, home of vicious water spirits – curving out of sight in a crescent of peacock blue. Beyond it floated the snowlit cone of Kailas. Its abrupt solitude, suspended 50 miles away above the brilliance of the lake, lent it the feel of something self-created. It was easy to imagine it holy to any people, at any age. Nothing – not a tree or a dwelling – showed around the lake. Its small monastery had been levelled into the rocks during the Cultural Revolution and never rebuilt.

But a little beyond it shone Lake Manasarovar, its sacred counterpart. An ancient holiness has freed these waters from intrusion. No one may fish here, and no one hunts its shores. As you descend to it you find its waterline thick with birds so tame they barely budge as you arrive. Black-headed gulls and redshanks pace along the sands; sandpipers wade the shallows, and Brahminy ducks float in pairs among the raft-like nests of crested grebes.

On these quiet shores I camped with a party of British trekkers who had come, like me, without faith, to a land sanctified by others. The nights around the lake are filled with portents for those who lie awake. The shooting stars are Hindu sky gods descending to bathe in the waters. An Indian pilgrim told me her night was disrupted by strange cries and flashing lights.

Hindus and Buddhists see different countries here. Tibetans believe that the Buddha's mother bathed in the lake before his birth, and its shores are still the haunt of hermits. But to Hindus, Manasarovar holds an intense, redemptive holiness. At dawn, I glimpsed a distant pilgrim knee-high in its purifying stillness. When I reached the headland where he had bathed, he was gone. Only a tiny packet of votive prayer-leaves floated in the shallows. Hindu lore is filled with the magic wrought by these waters. To bathe in them is to wash away the sins of all past lives; to drink them redeems the sins of a hundred others. In the watery rite of tarpan, the souls of pilgrims' ancestors are eased into eternity.

Two days later, as we reached the base of the mountain, my sherpa, cook and I stripped away our baggage to a single tent. The highest pass ahead was over 5,700m. As we went, the worlds of Tibetan Buddhist and Indian Hindu began to pull apart. The Tibetans set off cheerfully round the mountain as if it were a plateau. They twirled prayer-wheels and murmured mantras. Some carried babies on their backs, others shepherded little children. Their faith was practical and sensuous. Every rock formation was a god to them, or commemorated some mythic action. The earth itself was holy: the herbs it grew, even its dust. At the four little monasteries that staked out the cardinal points of the mountain, they offered incense or barley to a pantheon of deities. They prayed for better fortune – a son, another yak – and perhaps whispered to the fiercer mountain gods to expel the Chinese invaders. Hindus and westerners may take four days to complete the circuit. A Tibetan can do it in less than 36 hours.

But on our first day around the mountain, I was bemused to see scarcely any Tibetans. The day before, in a nearby valley, they had gathered in their hundreds round the sacred pole which is raised every year in the Buddhist holy month. But now, as we tramped in early morning along the Lha Chu, the River of Spirits, we saw the valley unfold in a 900m-high corridor where the Buddhist devotees had all but vanished.

This was unnerving. Neither my sherpa nor I could understand it. Ritual requires that worshippers circle the mountain clockwise, but almost the only people in sight were a few German and Austrian trekkers, and a trickle of dark-faced pilgrims descending the other way. At first I thought these pilgrims must be Bon, adherents of Tibet's pre-Buddhist faith, who worship the mountain walking anticlockwise.

But my sherpa said: "No. These ones are finished. They can't do it."

Then I realised that they were Hindus, returning the way they had come. They looked utterly spent, ashen-faced and unspeaking. Many were riding ponies led by local nomads, and were so swathed against the cold that their faces disappeared in coils of scarves. Some of them cradled little canisters of oxygen, which they discarded empty among the rocks.

A lone Indian woman stopped beside me, tightening her balaclava against the wind. Above her muffled mouth and dark glasses a scarlet tikka glowed on her forehead, like a lost hope. Her party came from Bangalore, she said, and nothing had prepared them for this.

"I don't know what happened to us. We went through government tests for our health – lungs, heart, everything … We numbered 68 when we started, but half of us turned back at Lake Manasarovar because of health – poor chests, coughing blood. Two of us died there, one a woman of just 40. Something happened in her breast. So we began to feel afraid."

The last of her party were passing behind us now. A woman in voluminous pantaloons leaned fainting on her horse, held up by her husband, walking beside her. He looked about to weep.

"We are not used to this cold. I suppose you in the west are used." The woman beside me was watching the blond trekkers marching up against the dark tide of her people. "I am full of sadness now. The rest of us went on and got up to 17,000ft (5,000m), then we couldn't climb further. Our nerve was broken. That is why we turned back before finishing our parikrama. I am very sad now, and rather ashamed."

She took off her dark glasses from eyes that sparked into life. "All the same, Lake Manasarovar was wonderful! We all waded in a little and washed its water over us, from the head down and – do you know? – we never felt it cold, but quite warm, because of its sanctity." She gave a fleeting smile. "At least we had that."

Since the 19th century, and doubtless long before, Indian pilgrims had been walking to Kailas pitifully ill prepared. Some arrived half-naked, begging. A few came hoping for death, which might lift them to salvation. From the 1930s, several thousand Hindus circled the mountain every year, until Chinese invasion sealed the passes. In 1981 a handful of pilgrims, chosen by Indian government lottery, were permitted to cross the border. Now they were being flown up from Kathmandu to Lhasa – an ascent of nearly 8,000ft in a few hours – then trucked three days west through the thinned air to Kailas. In the past few days, eight had died on the mountain.

We camped beneath the highest pass, and at dawn realised why yesterday the Tibetan pilgrims had seemed so few. They had started out long before sunrise, and gone far ahead of us. But now there were others mounting the track, many dressed in the sagging, ankle-length coats of tradition, sashed or belted in turquoise-studded leather. Some wore wafer-thin shoes or splitting trainers.

The stronger Hindus were ascending too, still buoyant with endeavour. For them, the rocks and peaks held a different power. The image of Tibet's founding saint offering a cake to Kailas became the monkey-god Hanuman, proffering incense. The invisible palace on the mountain top was not that of a Buddhist guardian deity, but of the great god Shiva, who destroys and recreates the universe in cosmic dance.

Among the scattered rocks 5,000m up, both Hindus and Buddhists shed a garment – or a lock of hair, even a tooth – in token of the past they are leaving behind, before mounting to the 5,700m pass of Tara, goddess of compassion, who will release them into new life.

It was beyond this flag-strewn pass, as I started down the knee-jarring drop into a valley 400m below, that a Hindu pilgrim called out weakly to me. For a while we sat together, exhausted by the climb behind us, wondering about the steepness of the descent ahead in the looming dusk.

"How far is it to the valley?" he asked. "How many hours?"

But I did not know. He was an Indian from Malaysia, used to soft coasts, rubber plantations. He said: "I didn't understand. I thought it would be easy. Yet here I am." He looked barely able to move. "The others have gone."

"Gone where?"

"Only seven of our group made it, out of 23 … We were told that if we bathed in Manasarovar, and finished the parikrama of Kailas, everything would be all right …"

"That you would gain merit? Perhaps moksha?"

"Perhaps." But he was haunted by those who had turned back, perhaps by the dead. And now it was the descent ahead that obsessed him. "Will there be horses at the bottom?"

"Yes, there will be horses." I was guessing, of course. "And the way will be level. It's a river valley. Beautiful."

But in his haggard face I saw no triumph at all.

Colin Thubron's To a Mountain in Tibet is published by Chatto & Windus, £16.99