Seven years ago, exasperated by living in a tiny London flat, the writer Tahir Shah enacted the cherished fantasy of stressed city dwellers everywhere by uprooting his young family and decamping to a stunning house on the outskirts of Casablanca.

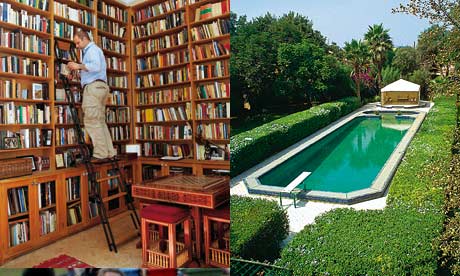

The house he bought, Dar Khalifa – the Caliph's House – is a sprawling residence with vast high-ceilinged rooms, fountains and tiled courtyards shaded by trailing vines. In the entrance hall hangs a portrait of Shah's great-great grandfather – a tribal warlord from Afghanistan. A swimming pool twinkles in the back garden.

Walking through the cool rooms, admiring Shah's extraordinary library – shelf after shelf filled with different editions of A Thousand and One Nights – it's hard not to feel a stab of envy, but it's tempered by knowing the travails he underwent to make the house habitable.

Shah recounts the process in his 10th book of non-fiction, The Caliph's House. He'd only the slenderest of connections to Morocco, remembering it fondly from childhood holidays spent there. He got the house for a knockdown price from a British expatriate who'd left it empty for nine years and was afraid a Moroccan developer would demolish it. But after the sale went through it turned out that the deeds had been lost, putting Shah and his family in imminent danger of eviction.

In addition to the usual problems associated with doing up a derelict building, Shah had to contend with Moroccan superstitions: workmen and staff believed djinns (spirits) had taken possession of the vacant house and wouldn't enter until they had been banished. At one point, a team of 24 exorcists was called in to sprinkle goats' blood in the haunted rooms.

"What do you think the going rate is for 24 exorcists?" Shah asks me, as he shows me round. "Four hundred euros! I thought it was a bargain. They were here for three days. They were out of control, cutting themselves. They loved it, they didn't want to leave!"

Shah shares with his late father, the Sufi scholar Idries Shah, a love of the traditions of Arab story-telling. In his writing and in person, his anecdotes have a folkloric rhythm, bouncing between triumph and disaster.

With 10 travel books and half a dozen documentaries on his CV, he's achieved an incredible amount in his 44 years but clearly measures himself against the standards of his father, who boasted of being able to write 10,000 words a day. The family counted the writers Robert Graves and Doris Lessing as close friends. Shah remembers the notoriously reclusive JD Salinger visiting their home in Kent in the 1970s. "He was very sweet. He stayed for a while and then he said he had to go home to cut the grass. He just didn't want any part of the world."

Shah lives in Dar Khalifa year-round now, with his Indian-born wife, Rachana, daughter, Ariane, nine, and son, Timur, seven. There are many extraordinary things about the house, but not the least is its location.

The drive to Dar Khalifa – a left turn from a leafy suburban street with handsome art deco houses – plunges you, as though through some kind of time warp, down a sharp dip and on to a dusty road that leads through the heart of a ramshackle bidonville, or shantytown. The rusty corrugated iron, mud-covered breeze blocks and miserable-looking livestock seem emblematic of third-world desolation.

The view from the roof of Dar Khalifa reveals the contrast at its starkest: the house and its grounds are an oasis of green with the sapphire pool at its heart; beyond the wall lies a dystopian landscape of smouldering rubbish and villagers fetching water from the town pump.

Shah is enthusiastic about his neighbours. "It's a functioning community. There's no crime. The thing that makes me cross is when people ask me if it's safe. I wouldn't let my wife and children live here if it wasn't."

I feel a flash of shame as he says this, because precisely the same question occurred to me the first time I drove through the shantytown. Later, I wandered through it at night and in spite of the contrast between the shabby slum and the tranquil luxury of Dar Khalifa, there was no sense of siege. In daylight, the bidonville is a motley jumble of houses, a few shops, a wonky-looking mosque and a man selling vegetables from a cart. Like shantytowns across Casablanca, it houses the low-wage workers without whom the city would grind to a halt. Still, it's the raw side of life in a developing country that most visitors and even many residents would prefer to ignore.

"The people who are most shocked are rich Moroccans," Shah says. "I've heard visitors shouting 'Shauma!' – shame. They think this is a side of Morocco that visitors shouldn't see."

During the period when Dar Khalifa stood vacant, resourceful residents of the bidonville had tapped into its water and power supply. During the first months of occupancy, Shah's water bill was €1,000 a month.

"I came back one time during Ramadan and the whole bidonville was lit up like a Christmas tree. I said to the caretaker, 'This is fabulous, it should always be like this.' And he gave me a funny look and said, 'Do you really?' I think he thought I knew they were stealing my electricity."

With the djinns banished, the house refurbished, and relations with the bidonville now clarified, Shah has turned his energy towards setting up a recycling project for the shantytown. A team of Americans is about to visit to advise on suitable schemes. He's paid a blacksmith to build a machine that will turn the glass bottles into glasses, and a hot press that will make discarded plastic bags into tarpaulins. The intention is for the recycling to be self-funding, but Shah has invested his own money in it and now he's letting rooms in Dar Khalifa to visitors to generate cash for the project.

The success of The Caliph's House has already made the house the object of literary pilgrimage – the American ambassador and his wife have popped out to take a look. Future visitors will be subsidising recycling.

For most writers – introvert, neurotic types – I imagine hosting paying guests would be purgatory, but Shah seems energised by novelty and drama. Sightseeing around Casablanca, we are accosted by an angry sorceress at a shrine who objects to my video camera. Shah is unfazed. He rhapsodises about the crumbling art-deco buildings in the city centre and over the roll-top baths in Casablanca's junkyards.

So far he's had half a dozen guests, all readers of his books. I tell him it's like going to Darrowby to stay with James Herriot, or Provence to stay with Peter Mayle. "So far, it's a bit like Misery. We've had the hardcore fans. I'm hoping we'll get more people who have no idea who I am, or who my father was."

How to get there

Royal Air Maroc (020 7307 5800; royalairmaroc.com) flies to Casablanca from Heathrow and Gatwick from £235 return including taxes. There are two suites at the Caliph's House (thecaliphshouse.com) costing €200 a night for two, including breakfast and dinner (children under 12 stay free).

Tahir Shah's The Caliph's House: A Year in Casablanca is published by Bantam Books, £8.99. Buy it at the Guardian Bookshop.