I'd been walking for an hour and a half along the "Zone Touristique" coastal fringe. Initially, I'd set out on a pre-breakfast stroll just along our hotel beach but found myself constantly seduced by the hint of another perfect bay or seascape beyond the next headland.

Jerba - the most southerly of Mediterranean resorts and thus the most reliable when it comes to early sun and a sea warm enough to swim in over Easter - has sensibly restricted its tourist development to the island's north-eastern corner and restrained vertical expansion to three stories. The style is North African and the colours almost exclusively Mediterranean blue and white. Architecturally, it is one of the most harmonious Mediterranean resorts I've visited.

After breakfast back in the hotel, I struck up a deal with a cameleer named Nabil. Despite being slobbery, bad-tempered beasts, camels these days seem to appear on virtually every beach in the Mediterranean. Hitherto, we'd never been tempted. But this was Tunisia with a baked-desert breeze sweeping up from the Sahara; and this was Jerba, where caravans still call in on their annual migrations. Therefore, it seemed only proper to be riding pillion behind my 13-year-old son Max. In front of us, our own caravan was being led by Nabil on foot with my 15-year-old daughter, Larne, riding solo.

With a lope and a slobber we passed French tourists playing boules and Germans hurrying back to their beach towels after breakfast. The coast was abuzz with windsurfers, canoeists and fishermen; the weather perfect. I was there last April, but Nabil claimed - and this was not the first time I'd heard it - that even in January Jerba was as balmy as Lisbon in spring.

Jerba receives a miserly eight inches of rain a year and 344 days of sun. And with the advent of direct flights, flying time is down to 3 hours. Jerba also happens to be Tunisia's most interesting resort and yet for some reason, it's still largely shunned by the British market.

Shaped like a jellyfish, 18 miles across at its most expansive, with just a single tentacle (the four-mile long Roman-built Kantara causeway) mooring it to the mainland, the island has a distinctive personality. Its resident population includes a renegade Muslim sect known as the Ibadia (close cousin to the Mzabites inhabiting Algeria's holy white Saharan towns) and a Jewish community which settled here from Palestine in 584BC. Some 700 years before them, Ulysses also reputedly called in on his long way home from Troy and discovered a people blissed out on the lotus flower (most probably the local hooch, legmi, which translates as "legless" and is fermented from palm sap). Most lotus eaters these days are German and come for the long, blond beaches.

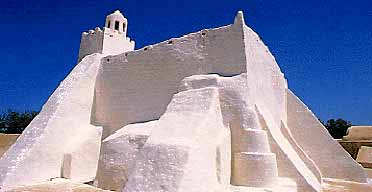

After a couple of days basking on the beach, we set out to explore an island as flat as Norfolk. As we swept over the island's highest mountain without noticing (only 182ft above sea level), we could see Africa, a hallucinatory shiver of heat across the causeway. Endless vineyards and fields of watermelons occasionally broke rank for a blazing-white mosque topped by an idiosyncratic Jerban squat minaret, or a lonely farmhouse fortified by cactus barriers and buttressed walls.

At Galella, we watched a man working a treadmill, dexterously shaping pots. He claimed the art had been handed down from Phoenicians who'd settled around the time of King Minos. Inside the restored synagogue of El Ghriba (it was bombed in April last year - an isolated seismic shock to the very peaceful islanders), an old wizened man tapped a sign that claimed the synagogue was founded in 586BC on a stone from the destroyed temple in Jerusalem. Dressed in thick woolly socks and an overcoat, he seemed even older than the synagogue itself.

On our return trip to the hotel, a policeman stopped us for a chat and, learning we were from England, asked me if I knew his friend Hocine who also lived there. In Jerba, everyone is eager to stop and chat. In the main town, Houmt Souk, I was deep in conversation with Haí, the owner of a Judaeo-Berber jewellery shop, when he confessed he'd spent four years teaching Hebrew and learning English at the Montefiore school in Maida Vale. As he reminisced, he continued engraving a solid silver brooch shaped in the Tunisian crescent with both Islamic and Jewish symbols. For Haí, the Hand of Fatima sitting alongside the Star of David was as natural as his own easy co-existence with the Muslim majority on the island. "Jerbans are very tolerant people," he said, "which is why there is still a community of 1,000 Jews living here 2,600 years after we first arrived."

Further into the town's souk, chickens grilled, puppets danced and men sat over endless mint teas at cafe terraces, or ran up cotton shirts on ancient treadle sewing machines. My daughter bartered for henna to decorate her hands and arms, my son stuffed himself on bambaloni (doughnuts) and my wife succumbed to the Berber carpets. Meanwhile, I was bidding for our lunch at the daily fish auction, from a man with a carnation behind his ear who held his catch aloft from a wooden chair perched on a raised platform.

For £2.75, I bought three golden-striped shelba (bream) and then followed the aroma of grilling fish across the street to a small arcade where, for a further £4, our lunch was cooked to perfection and served with flat bread, harissa, olives and tomato and onion salad.

Three days later, I chose the same succulent, firm fish 140km inland at a semi-desert hotel outpost, the Sangho, near Tataouine. We had left the hotel at 7am on our one-day Jeep safari, crossing the four-mile causeway to mainland Africa and endless orderly rows of olive trees first planted by the Romans. A few hours later, the soil became parched semi-desert, fit only for the hardy acacia scrub, and we arrived at the Berber troglodyte caves of Chenini, which burrow inside a high col above a stupendously inhospitable plain. Somehow, Chenini's dwindling population manage to grow figs, dates and olives in the ungiving earth. They also have an underground bakery and mosque as well as camel-drawn oil press.

As we scrambled up the scree, a boy with four plastic water containers greeted us, "Salamalicum". Surrounding him was an amphitheatre of fantastical cave-homes dug into weather-sculpted hills. The only other sign of life in the magnificent desolation were a few scrawny chickens scurrying in the dust. Then, suddenly, descending from the spur, an elderly man came into view riding a white mule. He was dressed in loose djellabah and riotous white beard, beneath which a straw hat had been fastened. We stood staring, mouths wide open, at the Berber Sancho Panza who, with considerably more grace, stopped, smiled and invited us into his home.

Passing beneath a palm lintel, we arrived in a courtyard in which a large door made from palm-tree trunks, and as dry and cracked as a rhino's hide, led into a single room carved into the hillside. The temperature plummeted as we entered Hedi's home.

The whitewashed barrel-vaulted room was maybe 14ft by 10ft and seemed to be pressing down on us. In his clipped French (he also spoke Berber and Arabic), Hedi showed us round his house without moving. There was a mat woven from palm fronds, a wooden trunk for his clothes, a Jerban amphora containing olive oil, a gypsum jar overflowing with dates, and olive branches protruding from the ceiling for hanging meat (the actual cooking was done outside using olive wood). It was an existence stripped back to essentials. The cave was a retreat from the heat and cold of the desert, and Hedi's lifestyle was little different to cavemen thousands of years earlier.

Hedi was 81 years old, claimed he could trace his family back 1,000 years and that the village had been around at least 1,000 years before that. From a tin box on the floor, he pulled out some metal stirrups that he said belonged to his great-great-grandfather. In his father's time, tribes of nomads raided the village, stealing the animals. Five years ago, 1,800 cave men and women lived in the village, now there were 500 as the ineluctable migration to modern towns and jobs accelerated. My children sat on the floor spellbound by Hedi's dancing eyes and incomprehensible language.

On our journey homewards, we detoured to an extraordinary fortified granary that stood like a termite mound on a hillside. At first, I couldn't make out what our driver was pointing to as the earth-coloured walls appeared as just another outcrop in the landscape. On the inside however, Ouled Soltane was a four-storey sci-fi fantasy of Hobbit cave-like dwellings and grain stores.

Like Douiret, it, too, appeared deserted apart from a man selling miniature Eiffel towers that he had conjured up from palm fronds. And then, bizarrely, two women suddenly appeared out of one of the tomb-like warrens as if they'd been resurrected. The two Australian friends were travelling slowly northwards after a fortnight exploring the Sahara. Unlike us, they were not now heading to wash off the desert dust back at one of Tunisia's many peerless beaches. Next on their itinerary was a tour of Tunis's Bardo Museum and Carthage. "Not too fussed about beaches to be honest," they explained. "We're a bit spoilt for them back home."

For we British, however, this is sadly not the case and for most of the rest of our stay, we stuck to our long sandy beach like limpets. Finally, when it was time to leave Jerba, I knew how Ulysses's crew members felt. "As soon as each had eaten the honeyed fruit of the plant, all thoughts of reporting to us or escaping were banished from his mind. All they now wished for was to stay where they were with the Lotus-Eaters." (Homer, The Odyssey Book IX).

Way to go

Getting there: Wigmore Holidays (020-7836 4999, aspectsoftunisia.co.uk) features seven nights' half-board at the three-star Jerba Beach from £549pp, or from £699pp staying at the five-star Movenpick Ulysse Palace (breakfast only; half-board supplement £15 per night). The prices include return flights and transfers. One-day Jeep safari carrying up to five people, £150.

Further information: Tunisian National Tourist Board, 77a Wigmore Street, London W1H 9LJ (tel: 020-7224 5598, tourismtunisia.com).

Country code: 00 216.

Flight time London-Jerba: 3hrs.

Time difference: +1hr.

£1 = 2.10 dinars.

· Paul Gogarty's The Water Road: An Odyssey By Narrowboat Through England's Waterways is published by Robson Books at £17.95.