For a couple of hours, the evening sun turns the dull brown rock of Mykonos to fool's gold. The narrow streets between the white cubist houses are full of people, from a distance all young, all beautiful, all impossibly fashionable. But that too is a trick of the light. When you look closely, you realise they are just the same people you stand next to every morning on the tube, miraculously transformed for a fortnight a year.

To most Greeks, the popularity of Mykonos is a puzzle: the island is an undistinguished lump of bare rock, the beaches are good but no better than many others in the Cyclades. The same could be said of the town, with its simple square buildings, the hard edges softened by hundreds of coats of whitewash, the doors and window frames all painted the same intense blue.

The island became popular in the 19th century simply because it was the nearest inhabited island to the archaeological wonders of Delos, but in the 1950s it became seriously fashionable.

The secret, if there is one, is that the islanders are very good at tourism. Few if any of the new developments could be called eyesores and the infrastructure works. Even with the population swollen by 80,000 visitors, you don't find any litter in the streets, the beaches are well groomed, and the islanders have a tolerance that goes far beyond financial self-interest or the obligations of hospitality. Mykonos was the first gay-friendly resort in Europe, and Paradise and Super Paradise are still the best-known nudist beaches in the world. Churches sit happily next to discos, and old women in black clothes thread their way entirely unconcerned between the naked bodies on the beach.

It is, of course, expensive, and it is a bizarre experience to sit in a club and realise that your drink cost more drachmas than you might once have spent in an entire summer in the Greek islands.

We weren't staying. It was just a flying visit, and next morning we would wake in another bay on another island. Lying in the harbour, almost unnoticed among the cruise ships and the flashy motor yachts was the Harmony G, as unostentatious as a stealth bomber and better than any of them.

Big cruise ships are too isolated from the outside world: you could be anywhere. The Harmony G has a draught of 2.5m so it can get into small bays and harbours inaccessible to large boats, and you can even dive off the top deck. At night, you can sit at the stern, just a couple of feet from the water, watching the white wake disappearing and enjoy that authentic Robert Maxwell experience.

Motor yachts are usually a triumph of money over taste, belonging to the world celebrated by two of the most dreadful songs in the entire history of popular music: Peter Sarstedt's Where Do You Go To My Lovely? and, even worse, the one about I've Been To Everywhere But I've Never Been To Me. The Harmony G's decor is bleached pine, black and grey. Slate blue and beige are about as wild as it gets, and the only pictures are middle-period Kandinsky prints, mostly black and white.

It is as comfortable as an ocean liner. The computer-controlled stabilisers are eerily effective, and it glides across the sea as though on rails.

The food, drink and service is as good as you would expect from a five-star hotel. Unusually for Greece, everything works. The bread and croissants are baked on board each morning for breakfast. The Austrian barman Niki knows everybody and everything but is far too polite to mention it.

Hydra is even more fashionable than Mykonos, and has been ever since Sophia Loren spent her holidays here in the 1950s. Later, Leonard Cohen came here to unwind, although possibly not quite often enough. The island is more fertile than Mykonos. It even has a few trees. The houses in the main town are elegant Venetian, all in perfect condition. The harbour front is an enormous outdoor café and, behind it, narrow streets and flights of steps climb steeply up the hill. It must once have been the kind of place where Sebastian Venable came to a bad end in Tennessee Williams's Suddenly Last Summer, but it has lost that weird, slightly sinister atmosphere that used to make Greek islands so distinctive. Henry Miller stopped off on his travels in 1939 to stay with the Greek painter Ghika. Now, there are dozens of art galleries in the main town, but none of the pictures are as good as Ghika's.

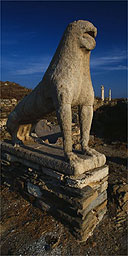

The most unchanged of all Greek islands is Delos, with only half a dozen new buildings in the last 2,000 years. In classical times, it was a sacred island. No one was allowed to be born, die or be buried there. Now, no one can stay the night, and all visitors have to leave by 3pm. Boats cannot moor within 500m of the shore, a precaution against theft. In the 19th century, most visitors went home with a few souvenirs. Some Italians tried to take away the giant head of Apollo, but even when cut into three it proved too heavy to load on to their boat, and it lies abandoned by the harbour.

Apollo was supposedly born here under a palm tree. When Odysseus met Nausicaa on Corfu, he compared her to a fresh young palm tree he had once seen on Delos shooting up beside the altar of Apollo. There is still a palm tree next to the ruined temple, but presumably not the same one. The kouros statues in the museum are as modern, simple and stylish as anything by Brancusi.

On the last evening of the three-day trip, we stopped off at Kea, which has the unsophisticated down-at-heel charm of the Greek islands I used to know and love. We walked along the road to Vourkari surrounded by the familiar chirrup of cicadas and the smell of dust and myrtle. There, we drank a couple of Metaxas at a taverna by the sea, then strolled back to the harbour where the grey ship was waiting to take us away, effortlessly, into the night.

Way to go

Getting there: Seafarer Cruises (01732 229900) offers seven-night "Classical Greek Cruises" on the Harmony G between April and October, visiting Kea, Delos, Mykonos, Santorini, Crete, Kythira, Monemvassia, Nauplion and Hydra with many optional shore excursions.Prices from £1,195pp (two sharing) including return flights from London to Athens, private transfers and half-board accommodation with all drinks except liqueurs and spirits.

Further information from the Greek Tourist Office, 4 Conduit Street, London W1R 0DJ (020-7734 5997). Time difference: GMT+2hrs. Country code: 0030. Flight time London-Athens: 3hrs 30mins. £1 = €1.59.